Last month I sat down with the Ukraine-based magazine Megapolis. I was honored to be interviewed by the publication about my career, life as a travel photographer, and my thoughts on photography in Japan. I was excited to see the interview published and syndicated across six print magazines in the Ukrainian market. For those who don’t read Ukrainian, I thought that I would provide the English-translation of the interview below. Thanks to the fine folks at Megapolis Magazine for the opportunity and their support.

When did you first come to Japan? What were your feelings?

My wife and I arrived in Japan during the summer of 2015. We made the move to Tokyo from Seoul and, after six years of living in South Korea, we were more than ready for a move. Tokyo had always been on our radar as a place we might want to call home, even for a short time.

I immediately felt refreshed in Japan. Tokyo gave me a renewed perspective on life. I felt joyous, relaxed, and ready for a new adventure. The change of environment gave me a needed jolt of excitement and purpose.

What made you move to Tokyo? So many people think of Japan as another planet. Personally, what was so captivating about this country?

We decided to relocate to Tokyo after receiving job offers to teach primary education at a prestigious international school. When the invitation came, my wife and I jumped at the opportunity.

Japan’s order, culture, history, food, and juxtaposition of ancient and modern elements were all magnetic. The Japan I have discovered is somewhat close to the version I had in my daydreams. After six years of living in Asia, Japan didn’t necessarily feel like another planet. In some odd way, Japan immediately felt like home.

You moved to Japan being already a professional photographer, didn’t you? How did your career develop?

I was a professional photographer when we moved to Japan but I wasn’t shooting full-time. For the first three years in Tokyo, I split my effort as both an educator and a photographer.

With two jobs, a wife, and a newborn son, I quickly worked myself into the ground. In 2018, I realized I was no longer capable of handling two jobs. There weren’t enough hours in the day. My health was suffering because of stress and fatigue. So, I put my passion for education on hold and directed all of my professional effort into photography.

With a less restrictive schedule I was able to start accepting commissions that, in the past, I had to regretfully decline. With my family’s blessing and support, I began working on travel assignments and commercial projects.

“Before you make a portrait, make a friend” — This is how you captioned a photo with a smiling woman in Vietnam. How long does it take to establish such personal contact, before making a photo?

The time it takes to make a connection with a person varies greatly and is largely situational. Establishing a connection could take seconds or hours. Generally, I don’t ask to make a portrait of a subject until I feel that there is some sort of rapport built. A simple gesture such as a smile might be enough for me to engage someone with my camera. Other times, I will sit, have a chat over coffee, or even meet a subject’s family before making an image.

A photographer’s drive to make amazing photos can, at times, diminish what portraiture is about at its core. When someone poses for a photo, they give a photographer the gift of vulnerability. I don’t want to flippantly take a portrait and move on. That ultra-quick pace makes interaction with a portrait subject one-sided and hollow. That pace is something I do my best to avoid.

Do you always want to “dig deeper” and learn the story of the person you are taking photos of?

Sometimes I meet a character and, honestly, just want to take their photo. That desire is selfish. Unless I am photographing for documentary purposes, I want to establish a positive connection with someone in order to add joy to their lives. With my camera in hand I often, admittedly, have tunnel vision and only think of the photograph I want to make. That outlook is directly opposed to my desire to make genuine connections with subjects.

Of course, I am, to varying degrees, interested in everyone’s story. A person’s history, their historical quilt, is how they became who I see through my lens. Usually, though, there isn’t enough time to truly get to know everyone’s deeper story. In the fast-paced world of assignment photography, time isn’t a luxury.

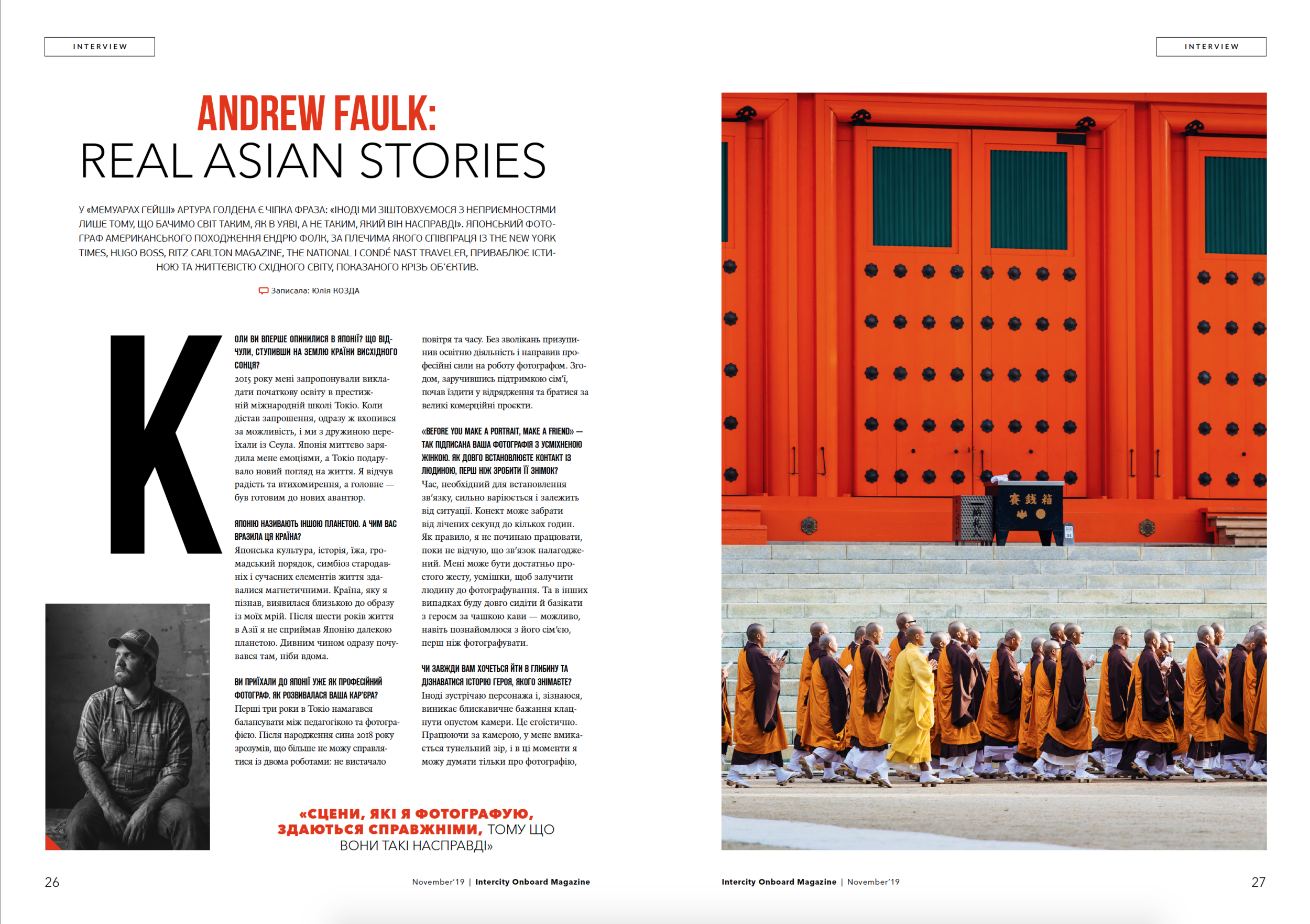

A sleeping man, hemmed dresses in Seoul, a portrait of a street vendor, vegetables at the market, swift waterfalls — it seems that many of your images are united by one central thing — they all feel real. Is this feeling difficult to achieve?

The scenes I photograph feel real because they are real. My hope is to make images that resonate with my own visual tastes. I photograph vignettes of the world as I see it, small representations of how I view my surroundings.

I don’t think it is hard to achieve what I do with my camera. It only takes a couple of months and a handful of Youtube tutorials to understand how to make a technically perfect photograph. Vision, on the other hand, is a never-ending process. The way I see the world is constantly evolving. Since this process is organic, it isn’t difficult at all to cultivate a visual aesthetic. It does, however, require an extreme amount of patience.

Have you ever met a character whose story deeply amazed you and perhaps even changed your life philosophy?

There have been subjects and situations that have given me pause and urged me to reconsider the ways in which I live my life.

I recall a rice farmer in Langkawi, Malaysia. He was methodical in his labor and kept a steady pace. I watched him for an hour or so, repeating his monotonous task. I made an image or two but was content to just watch the farmer work. From that situation, and others like it, I have learned to try to keep a consistently professional and personal pace; not too fast, not too slow.

What will never be in the lens of your camera?

I do my best to have a growth mindset. I want to explore what else is possible with photography. No matter what the photographic genre is, I want to approach new situations with a willingness to give any subject my best effort. I’ll never say never.

You tend to taste city life in small doses: rest your soul and switch off the buzz somewhere in the countryside, in the middle of rice fields. What, in your opinion, is the difference between provincial life and urban life in Japan?

I was raised in a small, rural area of the United States. At heart, I feel most at ease in the countryside. When I moved to Asia, I was just as shocked by the immensity of the cities as I was the new cultural environment. Now, after living in two of the world’s largest metropolises, I can appreciate city life.

Still, I have a need to be surrounded by the natural environments that resonate with my soul. Urban surroundings arouse the energetic and restless side of my personality while the rural areas of Japan soothe my need to be immersed in the vast spaces that reflect my more solitary, calm aspects.

There can be no travel pictures without travel. Are there places in Japan that you are ready to admire with your own eyes, without a camera?

First and foremost, I am a father and husband. I want to see more of Japan with my wife and young son without a camera in my hand. I would love to take trips with my family to the Izu Islands and to the northern shores of Hokkaido. I want to watch my son react to the various regions of Japan and to be fully present in those moments with him.

Does the camera always travel with you?

My camera always travels with me. Though, I am doing my best to leave the camera in the bag. I am becoming better at discerning when it is time for me to be a photographer and when it is time to just be myself, a husband, and a father.

With a camera held to my face, I become removed from the world. There are pros and cons to that aspect of photography. I recognize that there have been special moments in life that I have missed because I had my camera in front of me, hoping to get a good frame at the expense of the present moment.

Pictures created in collaboration with which company are you especially proud of?

Instead of pride, I feel fortunate to frequently collaborate with the New York Times (NYT). It is an honor to photograph Japan for one of my favorite publications. Many photographers dream of having a single image printed in the NYT during their career and I have been blessed to have photographed a large chunk of Japan for the NYT early in my journey as a photographer.

Is there a food cult in Japan? Does the principle “not photographed — not eaten” reflect the truth?

There is indeed a food cult here in Japan. Yes, sadly a part of this culture involves photographing meals. But this phenomenon isn’t solely found in Japan.

As a society, we have a documentary disease. Much of our time is spent snapping photos so that we can share our experiences with others. I question if this desire to “share” comes from a pure place. I think, more often than not, we take and share images of food to be noticed or validated in some way. I have yet to meet anyone in Japan, or anywhere else in the world, who takes photos of their meals strictly for the pure joy of photography or appreciation of the food.

Do pictures you take in the country of nanotechnology different from pictures captured somewhere in good old Europe?

I don’t think that my visual aesthetic changes when switching environments. I don’t approach locations differently. Whether Prague or Kyoto, Oslo or Tokyo, I simply take photographs of the things or scenes that intrigue me. Sometimes the colors or the details of a locale are inspiring. Perhaps the people or topography of a region are what stand out. I photograph whatever piques my interest.