Tokyo Photographer | 2020 Highlights

As I sit down to write my annual review, I am hyper-aware of the difference a year can make. Today, I am 30 pounds heavier than I was at the beginning of 2020 and, according to my wife, I desperately need a haircut. At this point, I have cleaned everything that can be cleaned, watched most of the titles in my Netflix queue, and have organized my hard drives in a variety of ways. I am now certain that experts are correct when they warn us of copious amounts of time indoors, sitting in front of screens, and eating our feelings.

I realize that my experience with 2020 is a fortunate one. I am alive and my family continues to be in good health. I am grateful to live in Japan where, for the most part, residents have taken the necessary precautions to keep themselves and those around them safe. Still, the emotional toll of COVID has been real and I am, like everyone else, ready to see an end to the saga we have collectively experienced.

Despite the fluid and unpredictable nature of 2020, I did had the opportunity to create some work, photographing a range of subjects both in Japan and beyond. As in years past, I am taking the time to reflect on my year as a professional photographer and to share some of my highlights from a twelve-month stretch none of us will ever forget.

I greeted 2020 on holiday with my family in Malaysia. With fireworks bursting in the sky, I silently declared that 2020 was going to be an unparalleled year of professional and personal growth. With the declaration in mind, I was ready to tackle whatever 2020 had in store.

Most of the images I made in Malaysia were of my son and wife, my favorite subjects. But during our trip, I also managed to point my lens at the streets, temples, and nooks of George Town, a UNESCO heritage town in Penang.

Teksen (George Town, Malaysia)

From Malaysia, I flew west to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. My agenda for my trip to Africa was to join thousands of pilgrims for Genna, the annual Ethiopian Orthodox Christmas celebration in Lalibela. I arrived in northern Ethiopia before the festivities began and stayed until most of the pilgrims were gone. In reflection, photographing the largest gathering of Christians in Africa was one of the most intense travel experiences of my life.

Check out my Lalibela Pilgrims series here.

With the pilgrimage over, I spent more time traveling through the Afar region of Ethiopia (one of the hottest places on earth). Though the land is inhospitable, the people were quite the opposite. Sleeping on the rim of an active volcano, hearing the night cries of hyenas, conversing with tribesmen, and meditative drives across Afar’s desolate landscape added to the already powerful trip.

Afar tribesman

Acid pool (Danakil Depression)

Personal security

Before returning to Japan, I forced a layover in Bangkok, my preferred transit hub. During my short stay, I photographed a series of images focused on Sukhumvit, one of the most clogged and bustling stretches of road in Asia.

Motorbikes on Sukhumvit (Bangkok, Thailand)

After more than a month on the road, I happily returned to Tokyo. I missed my family and was eager to get back to work.

As January came to a close, I caught up with client correspondence and began scheduling projects. I also got to see some of the work that I shot in the latter months of 2019 published by clients such as The New York Times, Condé Nast Traveller, Culture Trip, and Singapore Airlines.

Tokyo Tower for The New York Times.

Tokyo cityscape for The New York Times.

TeamLab’s Planets exhibition for Singapore Airlines

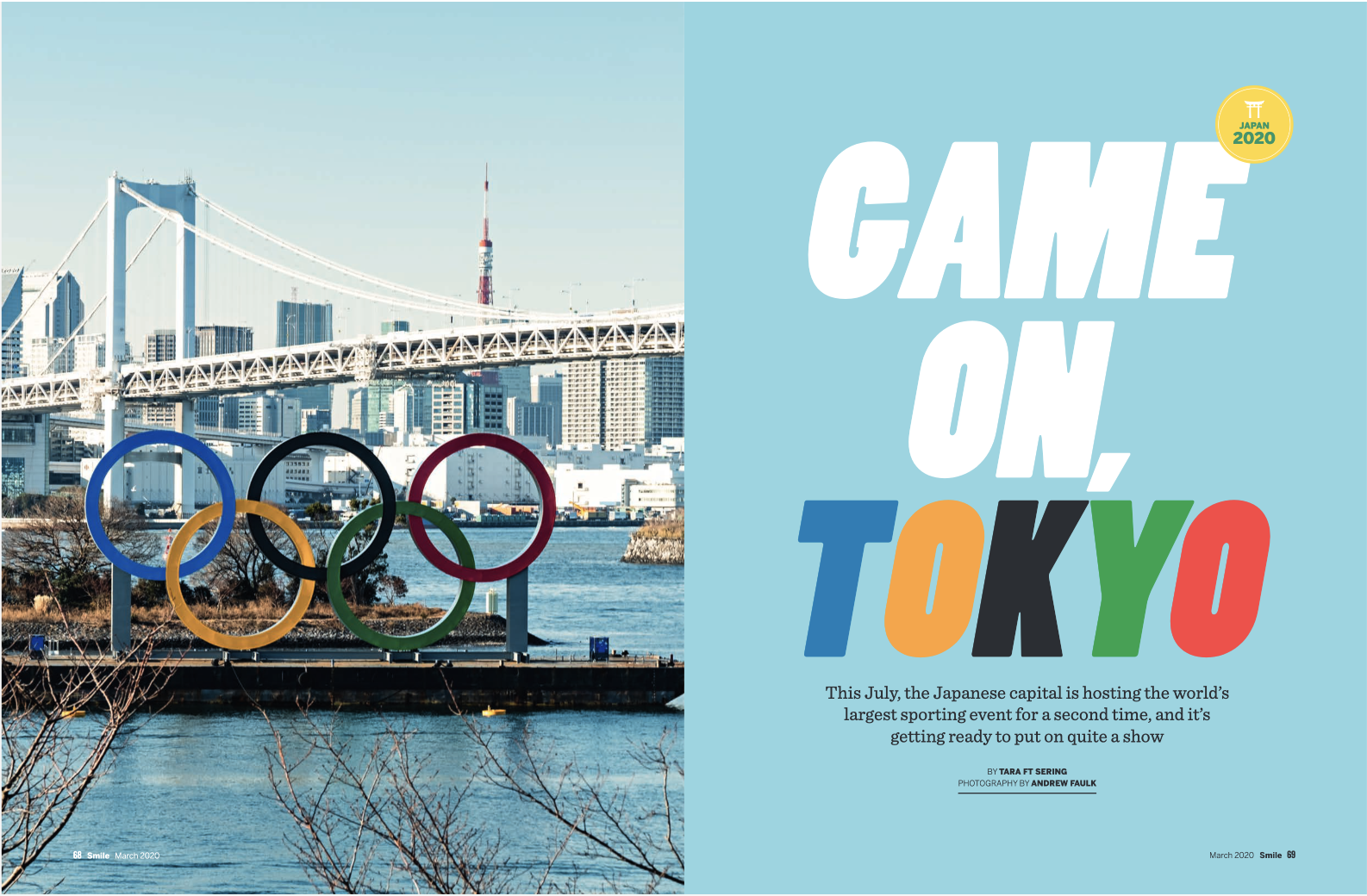

In February I shot a travel editorial for Smile Magazine highlighting the (then) upcoming Olympic Games. The assignment took me to some of the most iconic spots here in the Japanese capital but also allowed me to revisit some of the crannies I love as a Tokyo resident. While the final piece included mostly imagery of “iconic Tokyo,” I was happy to see the effort come to print.

Finished with the assignment for Smile, I hopped on a flight to Hokkaido for The New York Times to shoot 36 Hours in Niseko. It had been a few years since I had been to Niseko and I was thrilled to be able to hit the slopes for one of my favorite publications. I couldn’t have asked for a better assignment.

I kept both my camera and ski gear packed as my stint in the snow wasn’t over. From Hokkaido, I made my way back to Honshu and then onto Nozawa Onsen to cover the JAPOW (Japan powder) scene, again for The New York Times. Honshu had its worst ski season in a half-century but there was still enough snow to be able to enjoy a few gondola rides to the top of the mountain and complete the assignment.

With the string of editorials dusted, I switched mindsets from travel photography to commercial photography. I headed southwest to Kyoto to photograph Ebisuya, a newly opened machiya style hotel. For six days I worked with the boutique property to create imagery that reflects the style and sophistication Ebisuya will soon be known for.

Back in Tokyo, I was excited to see a feature I photographed of Naoto Fukasawa and his Tokyo studio showcased in SixtySix Magazine. I reminisced on how gracious the renowned industrial designer was during our time together and was reminded that, in the business of photography, one has to be okay with delayed gratification (I shot the piece in mid-2019).

By the end of February, I was exhausted. Fatigue aside, I was elated that my year in photography had started with such ferocity. And then the inevitable…

COVID-19.

A state of emergency was declared in Japan.

Lockdown.

Borders closed.

Within a matter of days, all of my upcoming assignments and commissions were either canceled or postponed. I went from having the busiest workload I can remember as a professional photographer to a completely clean calendar.

I was sure that COVID-19 would be akin to SARS, a pandemic I experienced a number of years ago. Surely this type of coronavirus was being hyped by the media for ratings and would quickly pass. I hoped that, like SARS, we would be cautious for a spell, and then, similar to other pandemic scares, it would pass.

Over the next several weeks, I had my fill of isolation, news, and masks. Going on a necessary trip to the grocery store felt like a major event, one mixed with equal parts of excitement and panic.

In mid-March, I set most things photography aside and picked up more household responsibilities. As I watched the pandemic spread west and engulf Europe, I realized that 2020 was indeed going to be a ferocious year, but not in the sense that I had imagined. I realized then that “the new normal” was here for the foreseeable future.

Photographers Damari McBride (New York) and Dylan Goldby (Korea) join me for a photography business discussion.

Aside from photojournalists, very few photographers had work coming in. The majority of us who found ourselves jobless and times were (and still are) tough. Regardless, photographers around the world did what they could to be productive. Some created portraiture series via Zoom while others started shooting family portraits from afar. Some photographers headed into the darkroom to experiment and others decided to spend their time reworking old images or creating content for their social channels.

I, on the other hand, couldn’t be bothered with producing any new work. I was depressed. During the spring, I didn’t feel motivated and lacked a creative spark. The muse was nowhere to be found though, to be honest, I wasn’t really looking.

After weeks of my pity-party, I just let go. I finally shed the self-inflicted pressure associated with the constant production and publication of imagery. I gave myself a bit of grace and entered a phase of quiet acceptance with the state of the world. I pulled back from social media and began to live life at a much slower and sustainable pace. The inertia was shocking at first but I soon realize that the slower pace was much healthier than the go-go-go I have lived for the past couple of years.

The spring work slump had another silver lining. While there were indeed bouts of cabin fever, I got to spend more time with my son than ever before. With school closures, I shifted from full-time photographer to full-time dad, a job that I was honored to have.

What little time I spent thinking about photography was to lend a hand to Travel and Leisure Asia, one of my favorite publications. Like photographers (and other creatives), travel-based platforms and publications were also suffering from a lack of demand. Considering this, I supplied the household title with a hefty amount of Japan and Vietnam based content.

After a couple of months indoors without a single job, I wondered if I would have another photography assignment in 2020. To my surprise, I heard from the NYT. With some restrictions easing, I was able to travel north to Saitama to make a few portraits of chef Naoyuki Arai. Chef Arai would be featured in the NYT’s Kitchen Gardens piece showcasing chefs around the world who had begun growing their own produce when the pandemic shuttered restaurants.

Chef Naoyuki Arai for the New York Times

As I suspected, the job for the NYT was a fluke and business again flatlined. Without a personal project in the works and my primary duty as a full-time dad still taking precedent, I shelved my gear but managed to continue my Today’s Inspiration interview series. During this time I was honored to learn more about the work of Marco Clarkson, Damari McBride, and Dylan Goldby.

Image by Dylan Goldby

Image by Damari McBride

Image by Marco Clarkson

Within months, COVID-19 had transformed and/or decimated the tourism industry (airlines, hospitality, travel photographers, etc.). Staple publications (i.e. Lonely Planet Magazine) began to go out of business. Media giants like INK Global (publisher responsible for most of the airline industry’s inflight magazines) halted publication and, for the titles lucky enough to stay afloat, the content was rapidly changing. Editors were forced to get creative about the stories they were assigning and running. The industry, in a short window of time, shifted dramatically.

An example of this shift can be seen in the one-off commission I received from Conde Nast Traveler China. My assignment was to photograph take-out food in Japan. The topic would have once been off-brand. But during a pandemic, the piece made sense for readership. My task was to showcase some of Japan’s takeaway options that many residents were choosing over their favorite restaurants. The hard part of the task? Well, that was to showcase the food in a sophisticated way, aligned with Condé Nast’s signature visual style.

Throughout the remainder of the spring, I didn’t have much business and before I knew it, summer began.

In June the publishing credits continued and I was finally able to share an editorial that I shot for Wired Magazine highlighting a recent collaboration between Spiber and The North Face. Shortly after the Wired piece was published I was able to share some behind-the-scenes work I shot for Ride, a travel-adventure show. Seeing this work used online reminded me of those off-camera conversations with Norman Reedus, Milo Ventimiglia, Ryan Hurst, and the rest of the Ride crew.

With international travel restrictions still firmly in place, I was eager to spend some time with my family out of Tokyo. Domestic travel restrictions somewhat eased and we decided to fly south to Ishigaki, one of the most sparsely populated places in Japan. the tropical island was the perfect place to take our facemasks off and spend some time outdoors. During the trip, I mainly used my camera to photograph the people I love most and an island that is as close to paradise as can be imagined.

Towards the end of the summer season, I shot several portrait commissions for individuals, couples, and families in the greater Tokyo area. But, for the most part, it was a quiet summer.

My first major commission in autumn was a commercial branding project for Divine Stream, a multi-faceted brand based on spiritual practice. The job took me throughout the streets of Tokyo and then to the Izu peninsula to photograph Reiko Dewey, the compassionate leader who heads Divine Stream’s Japan operations.

I filled the remainder of the autumn working with two major hotel brands. While I enjoyed shooting the architecture and lifestyle shots for the properties, my highlight of the stint was a bit more flavorful. On one assignment, I worked with the Four Seasons to create some food imagery with an editorial feel. I was excited and honored to be given the green light by the Four Seasons to shoot some of their dishes in any way I chose.

The ginkgos finally turned their striking yellow, my signal to begin the process of winding down the year. But before I cleaned my gear, I flew south to Kyushu for House & Garden, one of the UK’s leading lifestyle magazines. While I can’t share any cuts from the work I shot with one of Japan’s most accomplished artists just quite yet, I can say that the assignment was definitely a 2020 highlight and the perfect way to end my year behind the lens.

During the last two weeks of the year, I closed up shop. During the final stretch, I was honored to see some of my travel photography stock library used in Conde Nast Traveller (UK), CNT India, Afar Magazine, The New York Times, and more. Knowing that publications were still in need of imagery gave me some hope that the travel industry will, in time, return.

Nakano (Tokyo, Japan)

Bike Rider (Hoi An, Vietnam)

Sand Harbor (Lake Tahoe, Nevada)

With political turmoil, a raging pandemic claiming thousands of lives daily, and the future of the industry (as well as my place in it) in question, it goes without saying that 2020 has been a hell of a ride (one that I never want to take again).

But through the strife, I have learned a great deal about myself as a photographer and as a person. 2020 has forced me to examine my priorities. I am embracing what is truly important, what is meaningful in life (friends, family, ideals), and have learned to let go of the things that, frankly, don’t matter at all. While the year in photography was sparse in work compared to years past, it was a pivotal year as a photographer in Japan.

I wish everyone a peaceful and prosperous 2021. Stay healthy. Stay safe. Stay sane.

Tokyo Photo Journal #7

Postcard | Afar, Ethiopia

There was a clear separation in the groups. Us, the travelers, guides, and hired drivers slathering chocolate spread on thin slices of white bread after an early morning hike back to basecamp. Them, the gatekeepers of Erta Ale's roads and trails - Afar tribesmen gathered in clusters just meters away, self-segregated by an apparent social hierarchy.

Like so many times before, the dilemma of experiential travel presented itself. I questioned my place, our place as tourists. I questioned my intentions as a portrait photographer and the appropriateness of making images as a guest in someone else’s space, their home, their place of work. I also questioned why I was in Ethiopia in the first place. I didn’t really have an answer to either question.

The gentlemen enjoyed their conversation nearby. Even in the early morning, their vocal tones were jovial. I wanted to make photographs of the men who paid no mind to the tourists on their land. I wanted to be respectful, to not intrude. I wanted to continue to reinforce my belief that we should all be givers instead of takers. I wanted to avoid photographing solely for personal interests as I so often do. I wanted to interact with the tribesman, experience Ethiopia (as much as a short-term tourist can) in ways that weren’t strictly observational. I was conflicted.

I had some spare Instax film with me and knew that it would only take a few minutes to make a portrait for anyone who wanted one. The small photos could easily be used for Ethiopia’s mandatory national identification cards or, just to have. Offering Polaroids was, at the moment, the only way I could justify my decision to approach the Afar men standing nearby. Other than a smile, it was the only thing I had to offer.

I noticed several elders puffing heartily on cigarettes. Smokers tend to gravitate towards one another. Here, along the Ethiopia-Eritrea border, I hoped that this generalization held true. I wrangled a smoke from a crumpled pack of American Spirits crammed in the front pouch of my rucksack. I let the stick dangle from the corner of my mouth and decided to approach the men.

I asked for a match. To my delight, I was greeted with smiles and brought into the fringes of the circle, into the fold. There were matches for me as well as a language barrier, but our relaxed dispositions and curiosity for each other served as the real introduction.

We had a smoke or two and a motion-filled conversation about the state of my tennis shoes. In my periphery, I noticed that a translator from my tour group had shuffled over. He began translating without being asked - a gesture for which I was grateful. With his help, I related that I was able to make a portrait for anyone who wanted one.

At first, there were no takers. But after a bit of coaxing by his fellow tribesmen, an elder stepped forward. We moved to the side and the gentleman stood stoically for his portrait to be taken. Minutes later, he held the small sheet of film and others pressed close to see it. Soon, the rest of the men arranged themselves into a small line, each ready to pose.

After photographing the tribal elders and the more eager members of the group, I mentioned (through translation) that I had few film sheets left. A timid teen stepped forward and then, almost immediately, popped off into a lean-to shelter covered by a tattered tarp nearby. He returned donning a piece of dusty fabric that would serve as his makeshift necktie. I felt honored to photograph the lad and appreciated the thought he put into his time, albeit a short one, behind the camera.

After the experience, I am left wondering what place, if any, a photographer has in situations like this. I wonder if my disposition lets others know that I mean no them harm. I question my intentions and wonder if interactions like this one in northern Ethiopia leave the world a better place or erode it. I don’t have answers to these questions. Regardless, I was honored to spend a few morning moments with the men of Afar.

More From the Road

Somewhere In New Delhi

Kitchen Gardens | NYT Outtakes

As the world began to spiral into COVID-19 chaos, I heard from the New York Times. As a generalist photographer in Japan, I never know what kind of assignment will come my way and am always eager to see what the editors at the NYT photo desks have in store for me. For this commission, I headed north of Tokyo to Sakado, Japan where I was tasked to work with Naoyuki Arai, a talented chef participating in the newly launched Kitchen Farming Project.

What would it look like if out-of-work chefs dug in and built gardens? With the pandemic shuttering restaurants, chefs across the world decided to answer this question and planted “kitchen gardens.” From Williamsburg, VA (USA) to Ghana, roughly 3,600 participants like chef Arai answered the call and joined the Kitchen Farming Project, an initiative that serves as a loose “recipe: for a garden” conceived by Chef Dan Barber and further developed by farm director Jack Algiere (who created a step-by-step recipe, from sod-busting to seed selection).

The Kitchen Farming Project posed additional questions. What if a generation of cooks, chefs, and eaters emerged from pandemic-induced isolation never again looking at an ingredient list—or a farmer—in the same way? Is it possible to redefine roles in the food system, “not as end-users, but as engaged participants?”

Before the pandemic, chef Arai worked closely with an organic farm to stock his restaurant. With their help, he is now growing a large garden at his family’s home in Sakado. “Growing vegetables from seed has allowed him to observe everything about the process and can now even prepare dishes based on the various stages of ripeness. ‘ From sweet potatoes to green tea, Arai is exploring what is possible with the experience. “ I used to buy vegetables based on my schedule.” Now Aria is realizing that his schedule isn’t what is important but it is the “vegetables and the soil whose schedule should be respected.”

Now, as the gardener-chefs approach the end-of-summer harvest, they have a more robust understanding of the sweat toll required to grow each vegetable from seed and a more intense appreciation for the products they receive from growers. More, participating chefs are contemplating the roles they play in the larger food system. If Arai’s reflections are any indication, some of the questions posed by the Kitchen Farming Project are being answered affirmatively.

To learn more about the Kitchen Farming Project, check out the full piece in the New York Times (September 14, 2020).

More From Andrew Faulk

Tokyo Photo Journal #6

Tokyo Bay Bridge

Kichijoji at Night

Tokyo Construction

Asakusa - Bike Rickshaw Tout

Lines on Lines

Laundry

Oblivious to Cultural Norms

Asakusa Woman

River Bridges

Chuo Rider

Sensoji Smoke

Umbrellas in Ginza

Tokyo Taxi

Shibuya Station Mural

Bus Sleeper

Entrance

Under the Bay